Donald Trump's grab for the Panama Canal

The US has a big interest in the canal through which 40% of its container traffic passes

In his inaugural address last month, Donald Trump described the US decision to hand full control of the canal to Panama, in 1999, as "a foolish gift that should have never been made".

Trump also claimed that the Panamanian authorities overcharge the US ships for transit fees – and that "above all China is operating the Panama Canal". He added: "We didn't give it to China, we gave it to Panama and we are taking it back!" The president has often returned to this theme in recent months. Asked on 7 January whether he could assure the world he would not use military or other coercion to gain control of the Panama Canal or Greenland, Trump said: "No, I can't assure you on either of those two. But I can say this: we need them for economic security."

How did the US come to own the canal in the first place?

Because the US built it, between 1904 and 1914. Europeans had dreamed of building a waterway across the 51-mile isthmus between the Pacific and the Atlantic oceans since the early 1500s, but the terrain and climate are challenging – mountains, thick jungle, swamps, torrential rains, hot sun, debilitating humidity and plentiful tropical diseases. Ferdinand de Lesseps, who developed the Suez Canal, led a French attempt to build a canal between 1881 and 1889; 11 miles were built before the project was defeated by engineering problems, a shockingly high mortality rate and bankruptcy.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The US had a strong interest in establishing a route across Panama: ships from New York to San Francisco for instance, at that time, had to go via Cape Horn, which took months (though in the 1850s, a railway was built across the isthmus). The US secured the rights to build a canal – which, when completed, would cut the sea journey by half.

And how did it secure the rights?

Partly by gunboat diplomacy. The US government bought the French canal concession, but Panama was then a province of Colombia, and the US could not reach terms with its government. In 1903, the then-president, Theodore Roosevelt, supported an attempt by Panama to declare independence, and sent gunships to deter Colombia from intervening. Consequently, the new government granted the US open-ended use of the future canal, and sovereignty over a Canal Zone reaching five miles on either side – cutting a swathe through the middle of the new republic.

How was the canal built?

By the US army corps of engineers, using imported workers from the Caribbean. The engineers built six pairs of locks that raised ships from ocean level up 85ft to Gatun Lake – at the time the largest-ever man-made lake, created by damming the Chagres River with what was then the world's largest dam – and took them down again.

The canal is regarded as one of the greatest engineering feats of the 20th century. Most challenging of all was the Culebra Cut, an artificial valley carved through the continental divide. Some 400,000 pounds of dynamite per month were used to blast the rock, which was collected with steam shovels and taken to landfill.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

On 15 August 1914, the SS Ancon made the first official transit – travelling from ocean to ocean in less than ten hours. Native Panamanians were removed from the Canal Zone, which had been the most populous part of Panama, in part to make conditions more "hygienic", and it became effectively a US colony. This was a cause of lasting bitterness and protest.

When did Panama get it back?

Panama repeatedly tried to reclaim the canal and the land, particularly in the post-colonial era. The efforts culminated in the Torrijos-Carter Treaties in 1977, under President Carter. The Canal Zone ceased to exist in 1979; after a period of joint control, Panama took over the canal in 1999. It is now operated by the government-owned Panama Canal Authority, which recently built a new set of bigger locks, allowing the size limit for ships passing through to be expanded from so-called Panamax size (maximum 294 metres long) to Neo-Panamax (366 metres).

Today, between 13,000 and 14,000 ships per year pass through it – about 5% of world shipping – mostly travelling between east Asia and the eastern US. The canal is central to Panamanian identity and its economy. In 2024, the waterway earned $3.5 billion in profits; nearly 25% of Panama's income comes from it, directly or indirectly.

Does China run the canal?

No. It is run by the Panama Canal Authority. But two of the five ports adjacent to the canal, Balboa and Cristóbal, which sit on the Pacific and Atlantic sides respectively, have since 1996 been operated by a subsidiary of Hutchison Port Holdings, a Hong Kong-based conglomerate. Chinese companies, both private and state-owned, have also invested billions in Panama in recent years, as part of Xi Jinping's global Belt and Road Initiative.

The US certainly has a big interest in the canal, strategically and economically: 40% of US container traffic passes through it, and US trade accounts for about three-quarters of all canal transits.

How has Panama reacted?

President José Raúl Mulino said its dominion over the waterway is "nonnegotiable". "As president, I want to clearly state that every square metre of the Panama Canal and its adjoining zone is Panama's and will remain so," he said. China expressed its support for Panama's sovereignty. Russia warned the US against trying to exert control.

The US has invaded Panama before – to depose Manuel Noriega, in 1989. In theory, it could do so again. "All [Trump] needs is to land ten thousand troops and that's it," said Ovidio Diaz-Espino, a Panamanian commentator. "We don't have an army." However, Trump's threats to use military force are mostly seen as an attempt to assert US strategic influence, and to push for better terms. The Panamanian authorities ordered an immediate audit of Hutchison's port operations.

-

Trump’s ‘Board of Peace’ comes into confounding focus

Trump’s ‘Board of Peace’ comes into confounding focusIn the Spotlight What began as a plan to redevelop the Gaza Strip is quickly emerging as a new lever of global power for a president intent on upending the standing world order

-

‘It’s good for the animals, their humans — and the veterinarians themselves’

‘It’s good for the animals, their humans — and the veterinarians themselves’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The world is entering an era of ‘water bankruptcy’

The world is entering an era of ‘water bankruptcy’The explainer Water might soon be more valuable than gold

-

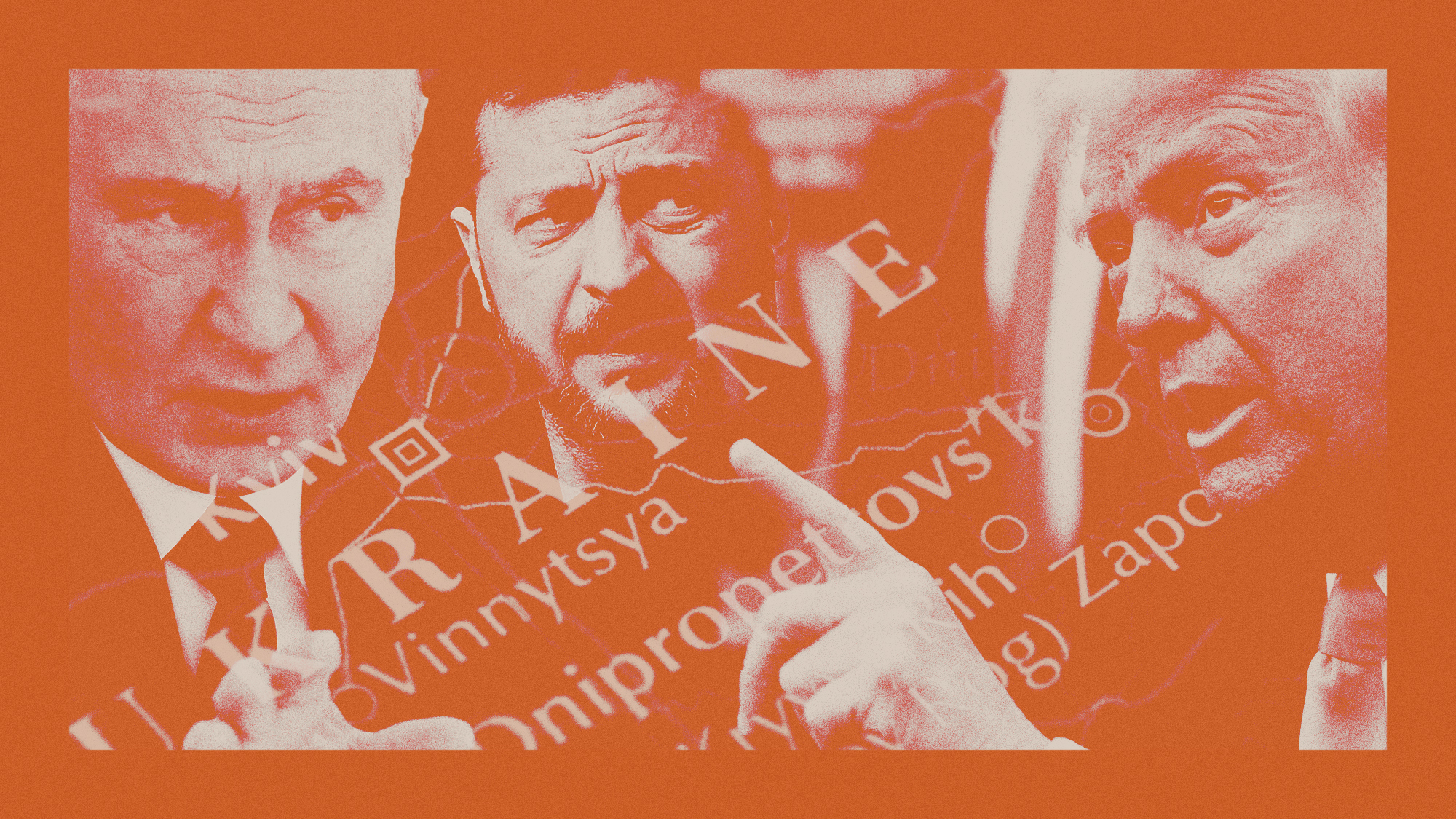

Ukraine, US and Russia: do rare trilateral talks mean peace is possible?

Ukraine, US and Russia: do rare trilateral talks mean peace is possible?Rush to meet signals potential agreement but scepticism of Russian motives remain

-

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mine

Panama and Canada are negotiating over a crucial copper mineIn the Spotlight Panama is set to make a final decision on the mine this summer

-

Trump backs off Greenland threats, declares ‘deal’

Trump backs off Greenland threats, declares ‘deal’Speed Read Trump and NATO have ‘formed the framework for a future deal,’ the president claimed

-

Iran unleashes carnage on its own people

Iran unleashes carnage on its own peopleFeature Demonstrations began in late December as an economic protest

-

How oil tankers have been weaponised

How oil tankers have been weaponisedThe Explainer The seizure of a Russian tanker in the Atlantic last week has drawn attention to the country’s clandestine shipping network

-

The rise of the spymaster: a ‘tectonic shift’ in Ukraine’s politics

The rise of the spymaster: a ‘tectonic shift’ in Ukraine’s politicsIn the Spotlight President Zelenskyy’s new chief of staff, former head of military intelligence Kyrylo Budanov, is widely viewed as a potential successor

-

Iran in flames: will the regime be toppled?

Iran in flames: will the regime be toppled?In Depth The moral case for removing the ayatollahs is clear, but what a post-regime Iran would look like is anything but

-

The app that checks if you are dead

The app that checks if you are deadIn The Spotlight Viral app cashing in on number of people living alone in China