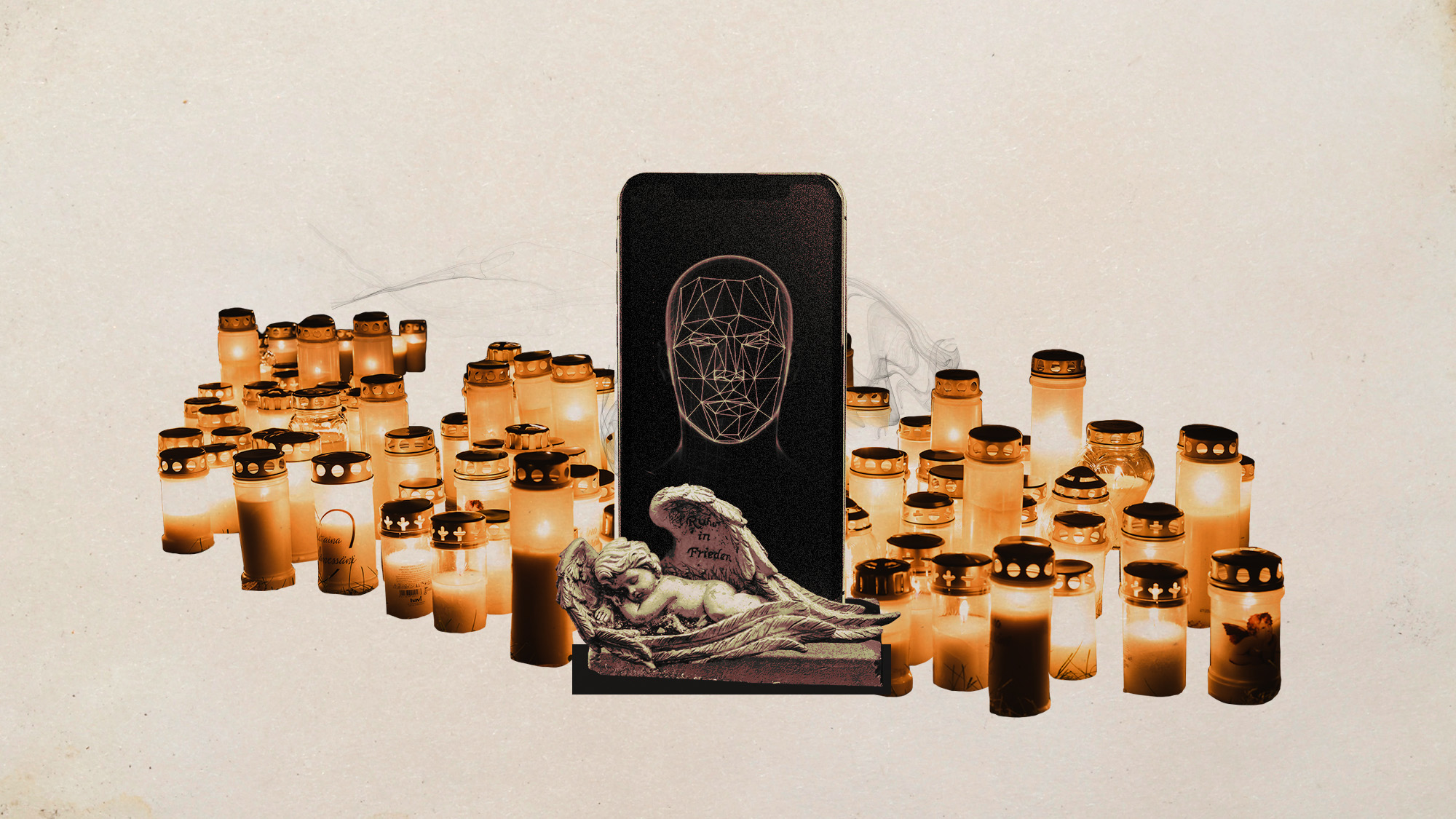

AI griefbots create a computerized afterlife

Some say the machines help people mourn; others are skeptical

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Some people who have lost loved ones are turning to a new industry to communicate with their dearly departed: using artificial intelligence “griefbots” that mimic a deceased relative. Many say these chatbots can be a helpful part of the healing process, but some tech experts are wary.

How do these chatbots work?

These artificially intelligent chatbots are designed to mimic dead individuals. While this AI niche started small, there are “now more than half a dozen platforms that offer this service straight out of the box, and developers say that millions of people are using them to text, call or otherwise interact with recreations of the deceased,” said Nature. The large language models (LLMs) that these griefbots train from often use “data such as a person’s text messages and voice recordings to learn language patterns and context specific to that person.”

This is the “same foundation that powers ChatGPT and all other large language models,” said Scientific American, but catered to a specific person’s characteristics. These griefbots have helped people process the emotional distress of losing a loved one. “After getting over the initial shock of hearing the incredibly accurate representation of his voice, I definitely cried,” Andy O’Donnell, who used a griefbot to speak with his deceased father, said to The New York Times. “But it was more of a cry of relief to be able to hear his voice again because he had such a comforting voice.”

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Why are they controversial?

While some have lauded the creation of these griefbots, “questions about exploitation, privacy and their impact on the grieving process are multiplying,” said The Guardian. People working through their grief may “maintain a sense of connection and closeness” by talking to their departed loved one, and “deathbots can serve the same purpose,” Louise Richardson, a member of the philosophy department at the U.K.’s University of York, said to The Guardian.

Griefbots can also be detrimental to healing, however, as they “can get in the way of recognizing and accommodating what has been lost, because you can interact with a deathbot in an ongoing way,” Richardson told The Guardian. People may have lingering questions or concerns they wish to ask a dead loved one, and now it “feels like you are able to ask them.”

Proponents of griefbots say they are not meant to replace a deceased person but are “marketed as tools to comfort the grieving,” said Natasha Fernandez at the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s Institute for Human Rights. While the “intentions behind griefbots might seem compassionate, their broader implications require careful consideration.” Possible exploitation of grieving people is one of the biggest concerns, as “grieving individuals in their emotional vulnerability may be susceptible to expensive services marketed as tools for solace.”

Providing these people with a paid chatbot “could be seen as taking advantage of grief for profit,” said UAB’s Fernandez. And if these griefbots are deemed to be “exploitative, it prompts us to reconsider the ethicality of other death-related industries” that are also driven by profit, such as funeral homes. Unlike funeral homes, though, most tech companies that build griefbots “charge for their services through subscriptions or minute-by-minute payments, distinguishing them from other death-related industries.”

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Justin Klawans has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022. He began his career covering local news before joining Newsweek as a breaking news reporter, where he wrote about politics, national and global affairs, business, crime, sports, film, television and other news. Justin has also freelanced for outlets including Collider and United Press International.

-

Hotel Sacher Wien: Vienna’s grandest hotel is fit for royalty

Hotel Sacher Wien: Vienna’s grandest hotel is fit for royaltyThe Week Recommends The five-star birthplace of the famous Sachertorte chocolate cake is celebrating its 150th anniversary

-

Where to begin with Portuguese wines

Where to begin with Portuguese winesThe Week Recommends Indulge in some delicious blends to celebrate the end of Dry January

-

Climate change has reduced US salaries

Climate change has reduced US salariesUnder the radar Elevated temperatures are capable of affecting the entire economy

-

AI: Dr. ChatGPT will see you now

AI: Dr. ChatGPT will see you nowFeature AI can take notes—and give advice

-

Can Europe regain its digital sovereignty?

Can Europe regain its digital sovereignty?Today’s Big Question EU is trying to reduce reliance on US Big Tech and cloud computing in face of hostile Donald Trump, but lack of comparable alternatives remains a worry

-

Moltbook: the AI social media platform with no humans allowed

Moltbook: the AI social media platform with no humans allowedThe Explainer From ‘gripes’ about human programmers to creating new religions, the new AI-only network could bring us closer to the point of ‘singularity’

-

Will AI kill the smartphone?

Will AI kill the smartphone?In The Spotlight OpenAI and Meta want to unseat the ‘Lennon and McCartney’ of the gadget era

-

Claude Code: Anthropic’s wildly popular AI coding app

Claude Code: Anthropic’s wildly popular AI coding appThe Explainer Engineers and noncoders alike are helping the app go viral

-

TikTok finalizes deal creating US version

TikTok finalizes deal creating US versionSpeed Read The deal comes after tense back-and-forth negotiations

-

Will regulators put a stop to Grok’s deepfake porn images of real people?

Will regulators put a stop to Grok’s deepfake porn images of real people?Today’s Big Question Users command AI chatbot to undress pictures of women and children

-

Most data centers are being built in the wrong climate

Most data centers are being built in the wrong climateThe explainer Data centers require substantial water and energy. But certain locations are more strained than others, mainly due to rising temperatures.