Cicadas are back with a vengeance

Beware the cicadapocalypse

Spring into spring with billions of cicadas! This year, the U.S. will see the emergence of two large broods of cicadas, which have not emerged simultaneously in more than two centuries. The ecological phenomenon could give rise to new species of cicadas and provide nutrition for several local animals. And while the insects are harmless to humans and animals, they will absolutely be seen and heard in the coming months.

Insect invasion

Billions of cicadas are expected to make an appearance in the East Coast and Midwestern U.S. this April as two broods of the insect emerge. Cicadas are periodical insects meaning they "spend most of their life underground in an immature nymph form before surfacing from the ground every 13 or 17 years for a brief adult life," NPR said. The two broods making an emergence this year are Brood XIX, or the Great Southern Brood, which emerges every 13 years, and Brood XIII or the Northern Illinois Brood, which emerges every 17 years. The prior is also the largest periodical cicada brood. "It's rare that we see this size of double-brood emergence," Jonathan Larson, an entomologist and assistant professor at the University of Kentucky, said to CNN. "We're talking about an absolute oddity of nature, one of America's coolest insects."

While double-brood emergence happens often, it has been more than 200 years since these two broods have emerged together, and it will not happen again for another 221 years. Periodical cicadas differ from annual cicadas, a brood that tends to appear every summer around August. Periodicals appear earlier in the year and not nearly as often. "It's like a graduating class that has a reunion every 17 or 13 years," Gene Kritsky, professor emeritus of biology at Mount St. Joseph University and author of "A Tale of Two Broods: The 2024 Emergence of Periodical Cicada Broods XIII and XIX," said to NPR.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

A constant buzz

While the emergence will be the "most macabre Mardi Gras that you've ever seen," according to Larson, the cicadas themselves are essentially harmless. The insects "don't sting or bite and are not poisonous," and can be a "great food source for birds and are nutritious for the soil once they decompose," Time said. They can be annoying though. "You should expect lots and lots of cicada exoskeletons to be covering your trees and shrubs," Larson said. "You should also expect to hear lots and lots of noise."

The cicadas emerge in order to breed and then die promptly after. The broods also consist of multiple species of cicadas. "The outcome of this will produce hybrids, and only the cicadas and Mother Nature know what the outcome will be," Mike Raupp, a professor emeritus at the University of Maryland's entomology department, said to BBC. Female cicadas lay eggs in trees, which could be harmful to young trees, but damage can be mitigated by using cicada nets. Despite this, "their emergence tunnels in the ground act as a natural aeration of the soil" and "provide a food bonanza to all sorts of predators, which can have a positive impact on those populations," according to Cicada Safari.

Geographically, the broods of cicadas may only see minor overlap. Brood XIII will emerge in northern Illinois, southern Wisconsin, eastern Iowa and northwest Indiana. Brood XIX will emerge in parts of Illinois, Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana and Arkansas. Areas in central Illinois are most likely to see both broods emerge around the same time. "If you're lucky enough to live in an area where these things are going on, get your kids out there," Kritsky said to NPR.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Devika Rao has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022, covering science, the environment, climate and business. She previously worked as a policy associate for a nonprofit organization advocating for environmental action from a business perspective.

-

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US ally

Syria’s Kurds: abandoned by their US allyTalking Point Ahmed al-Sharaa’s lightning offensive against Syrian Kurdistan belies his promise to respect the country’s ethnic minorities

-

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?

The ‘mad king’: has Trump finally lost it?Talking Point Rambling speeches, wind turbine obsession, and an ‘unhinged’ letter to Norway’s prime minister have caused concern whether the rest of his term is ‘sustainable’

-

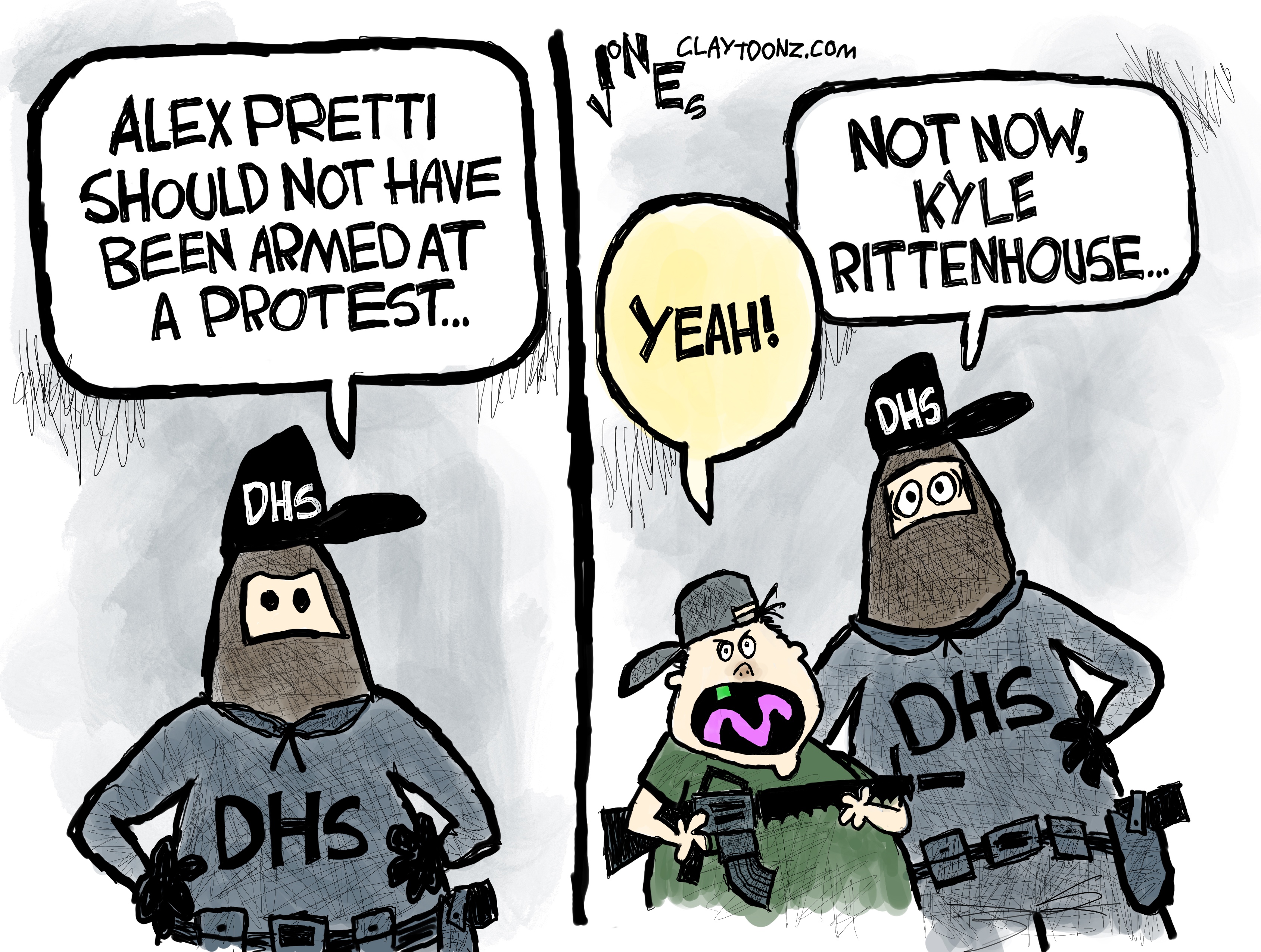

5 highly hypocritical cartoons about the Second Amendment

5 highly hypocritical cartoons about the Second AmendmentCartoons Artists take on Kyle Rittenhouse, the blame game, and more

-

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’The explainer Water might soon be more valuable than gold

-

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’Under the radar The gender gap has hit the animal kingdom

-

Why scientists want to create self-fertilizing crops

Why scientists want to create self-fertilizing cropsUnder the radar Nutrients without the negatives

-

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.

The former largest iceberg is turning blue. It’s a bad sign.Under the radar It is quickly melting away

-

How drones detected a deadly threat to Arctic whales

How drones detected a deadly threat to Arctic whalesUnder the radar Monitoring the sea in the air

-

‘Jumping genes’: how polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming Arctic

‘Jumping genes’: how polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming ArcticUnder the radar The species is adapting to warmer temperatures

-

Environment breakthroughs of 2025

Environment breakthroughs of 2025In Depth Progress was made this year on carbon dioxide tracking, food waste upcycling, sodium batteries, microplastic monitoring and green concrete

-

Crest falling: Mount Rainier and 4 other mountains are losing height

Crest falling: Mount Rainier and 4 other mountains are losing heightUnder the radar Its peak elevation is approximately 20 feet lower than it once was