The great uncertainty

We know less about the pandemic than we'd like to think we do — but we know enough to anticipate dangers and entertain worst-case scenarios

When St. Paul wrote that "we see through a glass, darkly," he meant it theologically: We cannot know the details of God's plan for our lives or human history. But the metaphor works just as well epistemologically — about what we can and cannot know about reality.

We aren't blind. We can see and know things about the world. Indeed, we can see and know much more about the world than we could in St. Paul's time, two millennia ago. Back then, plagues would arrive seemingly out of nowhere, perhaps anticipated by terrifying rumors of illness in nearby places. Often these rumors would be spread by visitors from those cities carrying the disease with them. The sickness would ravage communities, leaving death in its wake, with the survivors and the dying alike having little beyond petitionary prayers to protect them.

There is less darkness now. We know what viruses are and can test for them. We have a wide range of medicines, though not necessarily ones that can save us from the latest contagion. We can prepare and do things to protect ourselves. We can know that a specific virus is coming and, assuming foreign governments report the information honestly and accurately, know how many have so far died in the places it struck first.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

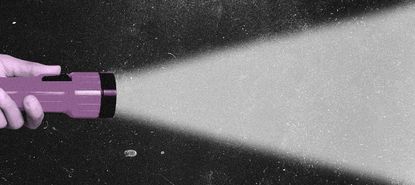

But how much more than this can we know? I mean really know, as opposed to the elaborate, mathematically sophisticated guesses we call modeling? Our models are our most powerful flashlights, attempting to illuminate the fog of uncertainty that surrounds us. But a light beamed into the mist only reveals so much. Sometimes it obscures even more by reflecting the light back into our eyes, worsening our blindness. That's why we're told to turn off our high beams, and to slow down instead, when driving through a dense fog.

What is a model? It's an attempt to operationalize a series of variables based on published studies, past knowledge, and experience in order to accurately predict the future. The model will also include a confidence (or uncertainty) interval — usually set at 95 percent probability, which is a way of delineating in mathematically precise terms a range of likely outcomes. So a model will provide a mean prediction as well as a range within which the outcome should fall 95 percent of the time.

How much light has been shed by modeling the coronavirus? Much less than one might think. Consider an assessment of two academic models of demand for ICU beds in Sweden. One predicted that demand would peak at around 22,000 beds, while the other predicted around 17,000. Meanwhile, the widely trusted Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) anticipated a demand of around 4,400 beds, with a confidence interval between 1,400 and 11,000. In reality, 450 ICU beds are currently being used in Sweden, and the total number has never exceeded 600. That's not even close.

The IHME model for the United States has also swung wildly over the past two months. In the early stages of lockdown, the model predicted something on the order of 100,000 deaths from COVID-19. Within a few weeks, that number had dropped to just over 60,000, with fatalities predicted to fall to near zero by the beginning of June. Today, the model has surged to 137,000 deaths, with fatalities falling to zero by the beginning of August. (The spread of likely outcomes currently ranges from 102,000 to 223,000 deaths.) All of this variation has taken place within the past eight weeks.

How could we be surprised? What we know about COVID-19 — a virus that didn't exist six months ago — is vastly surpassed by what we don't know. We don't know how contagious it is. We don't how widespread it is in the general population, which means we don't know how fatal it is. We don't know if or how much it will wane in warm-weather months or if it will return in a second wave later this year or next. We don't know how many strains there are or might be. We don't know if people become immune once they've been infected. We don't know how long any immunity might last, or if it will protect against other strains that emerge. We don't know if it will be possible to devise a vaccine to protect against it, or how effective it might be, or how long it will take to develop and disseminate one.

Neither do we know why some people are asymptomatic, why others have mild cases, why still others describe it as the worst illness they've ever experienced, why a few end up in the ICU, on ventilators, and die, why some develop much worse, longer-term medical problems in many different organs and systems of the body, and why some people continue to test positive for the virus long after their symptoms have faded. We don't even know what percentage of the population will need to be infected before herd immunity sets in, halting the spread of the virus without a vaccine.

The list of uncertainties is excruciatingly long. Those who build the models make informed guesses about the answers and then combine those hunches into predictions. We shouldn't be surprised when reality fails to conform to them.

Which would be fine if the models were constructed as an academic exercise by researchers trying to understand and make predictions about the contours of everyday life. Instead, they're being used as a baseline for emergency decisions that could have staggeringly high costs — with the possibility of hundreds of thousands or even millions of deaths pitted again economic devastation that plunges the entire world into the worst economic downturn in nearly a century.

In this respect, the past two months have been a highly compressed playing out of arguments about climate change and how to respond to it. For the past few decades, models devised by climate scientists have made alarming predictions about impending environmental devastation. These scientists and many journalists and activists familiar with their research have responded by saying that we need to make major (and potentially very costly) changes to our societies and economies in order to halt or reverse climate change and therefore avoid its worst consequences. But many others have responded with skepticism, thinking the economic and social costs of making dramatic changes are simply too great to undertake on the basis of guesswork.

The same dynamic is being played out right now with the pandemic, only with the threat and the painful consequences of acting against it unfolding in just a few months instead of over decades. Those favoring decisive action in the name of public health and accepting its terribly high economic costs put their faith in models despite the uncertainty on which they are based. On the other side, those more skeptical of the need to accept these high economic costs point in part to the uncertainty of the models, preferring to take their medical chances with significantly fewer public-health restrictions.

So far, the first camp has enjoyed much greater public support than the second. Given the risks, that's entirely understandable. Not to respond aggressively to a global pandemic would be a reckless gamble with people's lives. But when the outcome is uncertain and based so heavily on guesswork, isn't it also irresponsible to act in a way that's far more certain to produce extreme economic hardship, suffering, and pain?

That is the conundrum in which we find ourselves. We know less than we'd like to think we do — but we know enough to anticipate dangers and entertain worst-case scenarios. And once we've done that, it seems immoral not to do everything we can to forestall them, even at enormous cost.

It's hard to avoid injury when you're stumbling around in the dark.

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

5 carefully selected cartoons about the Trump-Daniels jury selection process

5 carefully selected cartoons about the Trump-Daniels jury selection processCartoons Artists take on a stress-free life, rare peers, and more

By The Week US Published

-

Loire Valley Lodges review: sleep, feast and revive in treetop luxury

Loire Valley Lodges review: sleep, feast and revive in treetop luxuryThe Week Recommends Forest hideaway offers chance to relax and reset in Michelin key-winning comfort

By Julia O'Driscoll, The Week UK Published

-

Myanmar: the Spring Revolution and the downfall of the generals

Myanmar: the Spring Revolution and the downfall of the generalsTalking Point An armed protest movement has swept across the country since the elected government of Aung San Suu Kyi was overthrown in 2021

By The Week Staff Published