William Barr's chilling vision of unchecked presidential power

This is the ultimate act of normalizing the Trump presidency

Even judged by the frenetic pace of the Trump era, the competition for most dismal bit of political news was especially fierce last week.

There were, of course, the impeachment hearings about the president's attempted extortion of a foreign power to get it to investigate his political rival. And President Trump's intimidating tweet about Friday's witness, former Ukraine Ambassador Marie Yovanovitch. And his pardoning of alleged war criminals. And his long-time confidante, Roger Stone, being sent to prison. And the Republican National Committee channeling large sums of money into the president's pocket by opting to hold its winter meeting at the Trump Doral Resort. And evidence that the senior presidential adviser in charge of immigration policy, Stephen Miller, is an avid reader and purveyor of white nationalist literature. And Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan repeatedly humiliating the president and the country during his visit to the White House.

Yet all of that moral debasement and rank corruption may pale in long-term significance in comparison to one more event that took place last week: a speech delivered by Attorney General William Barr on Friday at a convention of the conservative legal organization The Federalist Society.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Most of the early controversy about the speech has understandably focused on its furious partisanship. It is highly unusual for the senior federal law enforcement official in the country to adopt the strident language of political pundits. Yet there Barr was, denouncing "the Left" for engaging "in the systematic shredding of norms and undermining of the rule of law," suggesting that "so-called progressives treat politics as their religion" and "holy mission," and accusing the political opposition to the administration in which he serves of using "any means necessary to gain momentary advantage in achieving their end, regardless of collateral consequences and … systematic implications."

But this tirade was part of a larger argument. And it is that larger argument that made the speech truly important — and especially troubling.

Barr is a consummate Republican — a veteran of the Reagan administration's justice department, he also served as George H. W. Bush's attorney general from 1991-1993 — and a committed ideological conservative. The tension between ideological conservatism and the outlook and actions of the Trump administration has produced several years of tumult on the American right. With this speech, along with one on religion and politics that he delivered in October at the University of Notre Dame, Barr has positioned himself as the leading Republican aiming to heal the breach by advocating for the full assimilation of the presidency of Donald Trump into the conservative movement and the story it tells itself about the history of the United States and its democratic institutions.

In place of the discontinuity that many on both the center-right and center-left emphasize in comparing Trump to his Republican predecessors, Barr speaks of deep continuity between the American constitutional framers, the Reagan and both Bush administrations, and the Trump presidency. If Barr's account comes to be widely accepted on the right, the result will be a conservative movement and Republican Party that are less historically self-aware but potentially even more politically powerful than they are at present.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Barr's overarching claim in his Federalist Society remarks is that "the real 'miracle'" of the American founding is the "creation of a strong executive, independent of, and coequal with, the other two branches of government." In sharp contrast to "the grammar school civics class version of our revolution," according to which it was "a rebellion against monarchical tyranny," Barr asserts that by the time the American colonists took up arms against Great Britain, "their prime antagonist was an overweening parliament."

This is, to put it mildly, an unorthodox reading of the American Revolution. One reason why "grammar school civics" lessons emphasize King George III as the primary catalyst of the rebellion is that none other than Thomas Jefferson placed the king in the role of tyrannical usurper in the Declaration of Independence — the document in which the colonists sought to justify their actions before the world. After the ringing, universal rhetoric of the opening paragraphs, the Declaration sets out to defend the revolution by denouncing King George himself for attempting to establish an "absolute tyranny over these states." What follows is a list of 18 examples of such attempts, all of them beginning with the pronoun "He." The king himself, not parliament, is the provocation of the insurrection the American founders sought to lead.

But that's not the only historical sleight of hand to be found in Barr's speech. The attorney general also wants to claim that, having separated themselves from Great Britain and won their independence, the former colonies established a new form of government with a uniquely powerful executive in the office of the president, and that this was the founders' greatest achievement. While Alexander Hamilton, who favored a muscular head of the executive branch, might have agreed with some of these assertions, the other constitutional framers were far more cautious and concerned about the dangers posed by the presidential office. And the Anti-Federalists who opposed adoption of the Constitution in part out of fear of a tyrannical executive would have strongly dissented.

Barr waves all such historical complications away, blaming any and all concerns with presidential power on the "amusing," "breathless attacks" of "modern progressives." "Since the mid-60s," he claims, "there has been a steady grinding down of the executive branch's authority. ... More and more, the president's ability to act in areas in which he has discretion has become smothered by the encroachments of the other branches." In particular, Barr wants to push back against "the knee-jerk tendency to see the legislative and judicial branches as the good guys protecting society from a rapacious would-be autocrat."

Barr's criticisms of judicial overreach have some merit, in my view, so I won't quibble with them here. Far more disturbing are his attacks on congressional encroachments "on the presidency's constitutional authority." That these criticisms come during the presidency of Trump makes them especially remarkable. But that shouldn't prevent us from noting that presidents began pushing claims of executive privilege and prerogative into numerous new areas long before Trump. Since the September 11 attacks, in particular, presidents have pushed all kinds of boundaries. They have attempted to hold terrorist subjects in detention indefinitely, authorized and engaged in torture, surveilled the American people as a whole on a massive scale, and claimed a right to summarily execute Americans suspected of terrorist activities without charge or due process of any kind.

Congress, meanwhile, has almost completely abdicated its constitutional responsibility for declaring wars. Instead, presidents have been empowered under broadly worded authorizations of force to drop bombs on and deploy special operations forces and ground troops to countries all over the world in the name of fighting terrorism. Under much of the Obama and Trump administration, the U.S. has been fighting wars in at least seven countries (Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Libya, Somalia, Pakistan, and Afghanistan), all of them without a formal declaration of war.

And yet Barr would have us believe that "the president's ability to act" is being "smothered." And he thinks this at a time when the president he serves regularly pushes his office in the direction of outright criminality and abuse of power. Trump has flagrantly, almost flamboyantly, violated the Emoluments clause of the Constitution from his first day in office. He regularly warps policy by placing his personal interest ahead of the public good — which is what the ongoing impeachment inquiry is all about. The administration has responded to this inquiry by refusing to comply with congressional subpoenas or cooperate with routine efforts at congressional oversight. And of course, the president has also asserted as a blanket claim that the Constitution gives him the "right to do whatever I want."

The core message of Barr's speech is that when the president does these things, and when Republicans defend his right to do them and attack those who seek to stop them, they are doing the right thing, the patriotic thing, the thing the founders would have them do. To be a good conservative and a good American is to defend Trump's authority to do what he wants. Sure he's "thrown out the traditional beltway playbook," but "he was upfront about that beforehand, and the people voted for him."

Call it the ultimate act of normalizing the Trump presidency. In Barr's ideal America — one in conformity with the intentions of the constitutional framers — Trump would have been able to impose the travel ban, end DACA, add a citizenship question to the census, and make American foreign policy in Eastern Europe serve his personal whims and conspiratorial obsessions without having to face any pushback from Congress or the courts. No subpoenas. No irritating injunctions. No pesky Freedom of Information Act requests. No endless investigations. Trump would simply lead, and everyone else would follow.

This is a vision of the country in which the suspicion of executive power has been replaced by blanket deference to it. Obedience would be the nation's primary civic virtue. When Reps. Devin Nunes (R-Calif.), Jim Jordan (R-Ohio), Elise Stefanik (R-N.Y.), and other House Republicans obsequiously defend even the most egregious acts of presidential corruption and deception, they give us a glimpse of what such an America would look and sound like — just as Attorney General William Barr supplies the principles that would embed such deference in the nation's past — and encourage an American future defined by it.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

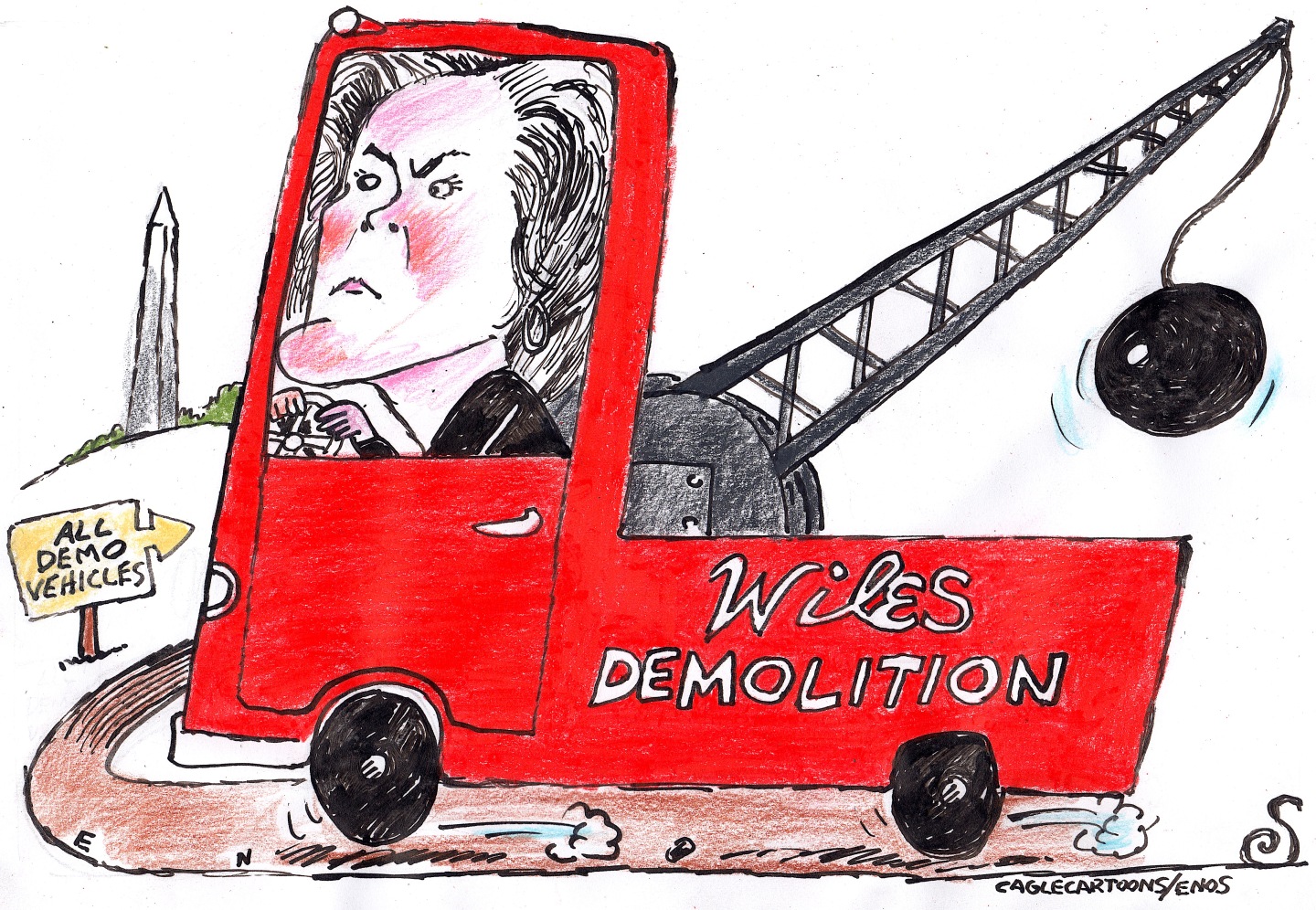

5 fairly vain cartoons about Vanity Fair’s interviews with Susie Wiles

5 fairly vain cartoons about Vanity Fair’s interviews with Susie WilesCartoon Artists take on demolition derby, alcoholic personality, and more

-

Joanna Trollope: novelist who had a No. 1 bestseller with The Rector’s Wife

Joanna Trollope: novelist who had a No. 1 bestseller with The Rector’s WifeIn the Spotlight Trollope found fame with intelligent novels about the dramas and dilemmas of modern women

-

Codeword: December 20, 2025

Codeword: December 20, 2025The daily codeword puzzle from The Week

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are US billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: who are US billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration