What the fierce liberal debate on free trade misses

Are poor countries really lifted out of poverty by free trade?

With Bernie Sanders' head-turning upset in the Michigan primary last night, it's worth noting the interesting thing that happened at the Democratic presidential debate in the state just a few days prior. Sanders ripped into Hillary Clinton for her support of past free trade deals like NAFTA. And Clinton didn't really fight back — she just kept trying to change the subject.

It used to be taken as gospel that free trade would make both Americans and people in other countries better off. The logic of free trade said that every national economy specializes in different things, so breaking down barriers and allowing freer trade should benefit everyone: China gets the goods and services we do best, and we get the stuff they do best.

It didn't pan out that way. Recent research confirms that trade with China wiped out at least 1.5 million American jobs between 1990 and 2007 — mainly manufacturing and other working-class jobs — that weren't replaced by anything. So the argument that free trade policies have made Americans better off is largely dead. But there remains another argument, which several liberal critics of Sanders have leveled, that even if free trade has hurt Americans, scrapping free trade deals would harm the global poor even more — especially the hundreds of millions of Chinese workers that have risen into the global middle class.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But this argument has problems too, thanks to a brewing intellectual crisis in the subfield of international trade economics. Marshall Steinbaum, a research economist at the Center for Equitable Growth, explained to The Week that trade economists have actually been enormously successful at building mathematical models of trade flows that hold up very well when tested against real world cases. "They're quite successful at explaining the changes in trade flows and who trades what with whom and how much that results from trade agreements and tariff reductions," Steinbaum said. "In a way it's one of the best subfields in economics. While empirical reality is notably absent from many parts of the field, that's definitely not the case for trade."

But something funny happened on the way there. Steinbaum explained that, according to the internal workings of the models, "trading a lot more doesn't actually increase people's utility all that much," which is economics-speak for "lots of trade doesn't make people better off." This is kind of freaking economists out, because the models are otherwise so good at predicting real world outcomes. "People see that as a puzzle, because a lot of economists just have it in their bones that trade is supposed to be super beneficial," Steinbaum continued. "Yet the model that's empirically successful says that it isn't."

The Occam's razor solution would be to simply conclude economists' bones are wrong, and freer trade doesn't actually make that much difference for rich or poor countries. Certainly, China and other developing countries have been pulling themselves out of poverty over the same time period that globalized free trade has taken off. But that could just be a coincidence.

It's worth pausing here to think through how international trade works. Ignore money for a moment, and remember that international trade basically boils down to people in Country A making goods and services and then shipping them off to Country B. But if Country A is poor and trying to develop, why would it do that? Wouldn't it want to keep those goods and services within its own borders, to build up its own wealth and the well-being of its citizens? In fact, wouldn't it want to bring in more goods and services from elsewhere, on top of keeping its own production, in order to build up even faster?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

This is why it's downright bizarre for supporters of free trade to claim that the ability to export to America was crucial to China's economic rise.

Now bring money back into the mix. When Country A sells its goods and services to Country B, it gets Country B's dollars in return. But Country B's dollars are also tied to that country's debt and stock market (among other things), meaning Country A is basically investing in Country B. This is a mathematical truism of economics; it cannot be otherwise. So any country that's running a net trade surplus — that's exporting more stuff than it's importing — also has to be a net lender of capital to the rest of the world. In other words, because China has been running a net trade surplus with the U.S. (and the world), it has also been investing in the U.S. A poor country is lending capital to a rich country — that's completely backwards!

It's also why textbook economics generally assumes poor and developing countries should be in trade deficit with the rest of the world and thus a net borrower of capital, and why rich developed countries ought to be in trade surplus and net lenders. That's what you'd expect. And this is something the pro-free-trade argument has really lost sight of — that the trade relationship between the U.S. and China in particular is deeply unhealthy.

This doesn't mean we should start ripping up trade deals and slapping tariffs on everything. China, for example, would have industrialized and moved its rural workers into its more productive urban centers regardless; if freer trade wasn't the prime cause of its economic rise, then China's breakthrough — if partial — embrace of market institutions in the same time frame is a likely nominee. But the freer exchange of goods certainly gave them access to American technology, business models, industrial know-how, and more, so they could develop faster and not have to reinvent any economic wheels, as it were.

It's also the trade deficit — not trade per se — that creates the drag on aggregate demand here in America, and makes it harder for us to create enough jobs for everyone. We can export and import with China all we want, and as long as those flows net out to roughly zero (or a trade surplus for America), there's no harm, no foul. We can address that with better rules about currency manipulation, rather than restricting trade with tariffs. And even if there is a trade deficit, we can make up the loss of demand with the right fiscal and monetary policies.

Both Clinton and Sanders should be talking about this point a lot more. But if what happened in Michigan is any indication, voters who've been upfront and personal with the effects of free trade think Sanders is talking about it enough. And their grievance is a whole lot less wrong than many of the experts assume.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

15 years after Fukushima, is Japan right to restart its reactors?

15 years after Fukushima, is Japan right to restart its reactors?Today’s Big Question Balancing safety fears against energy needs

-

The Week contest: Farewell, Roomba

The Week contest: Farewell, RoombaPuzzles and Quizzes

-

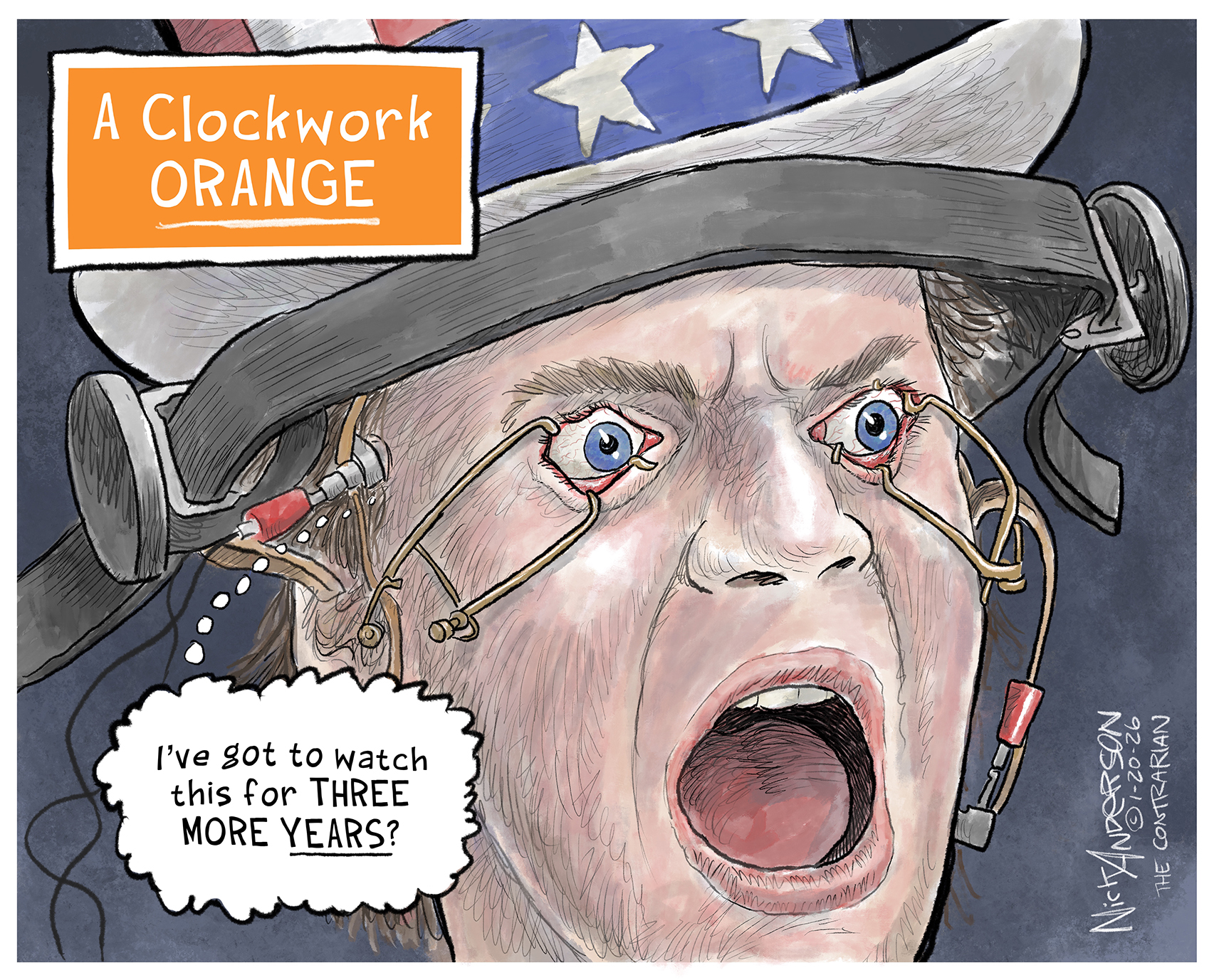

Political cartoons for January 21

Political cartoons for January 21Cartoons Wednesday's political cartoons include a terrifying spectacle, an absent Congress, and worst case investments

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred