The world's most brutal sport

In Florence, men play a centuries-old game that often leaves them bloodied and badly injured

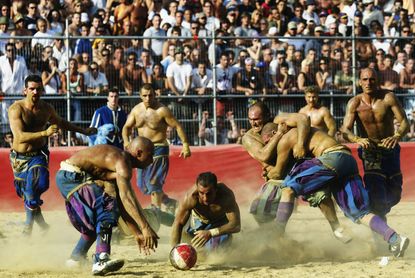

ON A RECENT Tuesday, about 24 hours before he jammed his fingers into another man's nose, dropped his elbow across another man's neck, and put another man's feet where one's ears are supposed to be, Rodrigue Nana considered, just for a moment, the basic notion of fear.

"Do you want to know what I am afraid of?" he asked, his fingers tracing the meaty scar above his left eyebrow. Nana, a Cameroon-born transplant to Italy, leaned forward, as if to share a secret. "I am afraid of showering."

He did not laugh. Neither did any of his teammates sitting nearby. This was not a time for joking; Nana and the rest of his team were about to begin their last training session before their final match of calcio storico, a centuries-old competition that features very few rules and the sort of human wreckage generally associated with the days of the gladiators.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Nana and his friends have endless stories. There was the player whose ankle shattered at the bottom of a dog pile. The one who went into a coma after being punched in the back of the head. The guy whose ear was bitten off in the middle of a scrum. In one game, Nana had his shaved scalp cut open the way a letter opener slices an envelope.

"The thing is," Nana continued, "when you're playing, you don't feel any of it. But then you calm down and take a shower. And that is when everything starts to burn."

The other men, who ranged in age from their late teenage years to their mid-40s, nodded. None of them could say why they were sitting on dilapidated benches beside a raggedy field in Florence; could not put into words what made them spend four months preparing to play, at most, two games that almost always require some form of medical attention afterward.

They just knew that they felt they had no choice. For many, it was simply hard-wired history. This grand Italian city has four historical quarters, each with a church at its center, and calcio storico, which is believed to date from the 15th century, is played by one team from each neighborhood. To play for your neighborhood team — to wear the Verdi (green) of San Giovanni or the Azzurri (blue) of Santa Croce or the Bianchi (white) of Santo Spirito or the Rossi (red) of Santa Maria Novella — is, as Niccolò Innocenti of the Verdi put it, "deeply Florentine."

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

It is like a war — no one does it for the money.

"When I played for the first time, the sensation I had was one of truly being a man," he said.

For others, though, the attraction is more primitive. With two teams of 27 players placed in a sand pit and told to do whatever is necessary to get a ball into the other team's end zone, the sport is a strange mix of U.S. football, rugby, and street fighting. Watching it live, the more direct comparison might be to the children's game Red Rover, but with punching and tattoos.

Brutality is everywhere. No player has ever died during calcio storico, but Luciano Artusi, a former director of the body that oversees the games, conceded that "we have had a spleen removed." Filippo Allegri, one of the on-field medical attendants, said that his group generally expects that seven or eight players from each team will not finish any given game, and recalled, without prompting, that 10 players, or about 20 percent of the total participants, required hospitalization after a particularly brutal final in 2013. There are no substitutions, so exhaustion is common.

All of this might make more sense to the average outsider if there were millions of dollars (or at least enduring fame) on the line. But players are not paid in calcio storico, and there is no significant prize. The winning team used to receive a calf from Tuscany — butchered, not live — but now the champions simply have the cost of their postgame dinner picked up by the federation. There is not even a medal ceremony.

"It is like a war — no one does it for the money," said Nana, who plays for the Bianchi. "You do it because you feel an obligation to fight." He shrugged. "So you fight. And if you come back alive, you get drunk and talk about it."

THE PLAYERS OF the Bianchi gathered in the early afternoon of a recent Wednesday. They listened to their coach give a lecture about strategy for that evening's match and then dressed in their uniforms: historically appropriate striped pants and white T-shirts. (For many, these shirts were only temporary; most players play shirtless.)

Some wore sneakers; others chose soccer cleats. Each player wound layers of heavy packing tape around his waistband, to make it more difficult for an opponent to grab on.

After a bus ride to the city center, the players from the white team, representing the southwestern part of the city, and their opponents, the green team from the northeast, walked into the temporary arena set up on the piazza in front of the Basilica of Santa Croce. On Feb. 17, 1530, Florentines played calcio storico in this piazza while their city was under attack; on this Wednesday, the sudden blast of a cannon (along with a referee's whistle) was the signal to begin the match, and the crowd of more than 4,000 fans roared in anticipation.

"It's not just a rivalry between neighborhoods," said Federica Guzzo, who cheered for the Verdi, "but a true visceral passion that is passed on generation to generation."

The air in the piazza smelled of smoke and sweat. In front of the basilica, with the statue of Dante casting its long shadow alongside the steps, residents of the nearby buildings opened their windows and charged tourists for a spot with a view. Others hung out the windows themselves. One woman, clutching a baby, sat on a rooftop with her legs dangling off the ledge.

The game began slowly, cautiously. The sand on the field is nearly 16 inches deep, so players prowl more than patter. Despite calcio storico's relative simplicity — a team scores a point if it gets the ball anywhere in the area behind the end zone's wall and can receive half a point for a variety of other, less common, plays — there is some legitimate strategy involved.

Every game in calcio storico lasts 50 minutes but feels like 500.

Forwards from the Bianchi sporadically made weaving runs into the Verdi defensive area, drawing attention from defenders and opening space. The Verdi, on the other hand, played more deliberately, trying to clear routes through the Bianchi defense with brute strength.

It was not apparent if most of the spectators understood much of this maneuvering (or, frankly, if they cared). They wanted blood, and it came quickly: An eight-player melee after two minutes of play resulted in at least one possibly broken nose and the ejection of a player from each team. The perpetrators' crimes? It was not immediately evident, but there are a few token rules designed to avoid complete chaos — no blindside punching, no hitting a player on the ground, no foreign objects — and the referee, who also wears a period costume and carries a sword, apparently had noticed a violation.

"Trying to knock other players out of the game is a very basic strategy," said Fabrizio Valleri, a forward for the white team. "If we knock one out, of course, it gives us a man advantage. That can mean everything."

Valleri did not mean he hoped to literally render someone unconscious — though that does happen. He meant teams often try to injure an opponent to the point where he cannot continue. And as the game progressed, it seemed more and more likely that that would occur.

Scuffles broke out in every corner. Men coated in sand swung wildly. Medics rushed from the sideline to wrap bandages and swab abrasions. One player doubled over after taking a cracking shot to the ribs. Another player's stitches, which were supposed to be holding together a wound sustained in the semifinals, burst open, allowing blood to stream down his face. At one point, a forward for the Bianchi gallivanted into the Verdi defensive area and was met with a punishing tackle, chest to chest. The colliding bodies made the sound of a cowboy cracking a whip across his horse's back.

Every game in calcio storico lasts 50 minutes but feels like 500. Before Wednesday's game was even halfway completed, the players were languishing, the fans were frothing, and the field was covered in shredded shirts and crushed plastic water bottles and bits of tape that had been ripped from the players' pants or wrists. (Players are no longer allowed to wrap their hands because, several years ago, one team had its players wrap their knuckles in dry plaster, complete the prematch inspection, then dip their hands in water just before the match began so the plaster would harden. The resulting carnage, one player recalled, "was tragic.")

The Verdi, led by a calcio storico legend, Gianluca Lapi, led early on when it scored a half-point for throwing the ball into the end zone but having it deflected on the way. The Bianchi's fans moaned, but by the half-hour mark their mood had brightened on the strength of two caccias, or goals.

In a sport slowed by constant clutching and grabbing, this constituted serious momentum. Infused with bravado, the white team's fans chanted, "Bianchi! Bianchi!" They then suggested a particularly obscene activity for the Verdi fans to consider attempting.

The rest of the game went similarly. By the final few minutes, the Bianchi led, 4½-½, and the ejected players from the Verdi were anxiously smoking cigarettes behind the fencing. At the final whistle, the Bianchi fans poured on to the field. At least one of the Verdi players sank to the sand and wept.

The moment lingered. All around the piazza, Verdi players moped while white T-shirts mingled, the shrieking and shouting interrupted only when an official called out the names of players who had been selected for drug testing. (Anti-doping is taken seriously, several players said, though no one could forget the unlucky player, years ago, who received a phone call after submitting his sample informing him that he — or, more likely, the woman who had surreptitiously provided it — was pregnant.)

Finally, the dope testing was over and everyone slid out the side of the arena into the streets. Allegri, the medic, and his crew looked happy enough — this was the first time in recent memory that a stretcher had not been required during a game — but the Bianchi, despite several of their members limping noticeably, were jubilant. Lorenzo Taddeucci, who had scored one of the caccias, bounced back and forth from curb to curb, clapping teammates on the shoulders and holding his fingers in the air.

"I don't know how to describe this," he said. "It just feels right."

Taddeucci shrugged. The players did not care that they had made no money, did not care that they had won no giant trophy. They cared only that they would remember this Wednesday. They cared only that they had survived.

Originally published in The New York Times. Reprinted with permission.

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

-

Solo travel: the 'ultimate indulgence in 2024'

Solo travel: the 'ultimate indulgence in 2024'The Week Recommends Why more of us are choosing to go on holiday on our own

By Adrienne Wyper, The Week UK Published

-

'Stormy Monday for Don'

'Stormy Monday for Don'Today's Newspapers A roundup of the headlines from the US front pages

By The Week Staff Published

-

6 queer poets to read whenever but especially now

6 queer poets to read whenever but especially nowThe Week Recommends April is National Poetry Month

By Scott Hocker, The Week US Published