Why Holy Thursday is so important to Christians

Several religions believe in a single utterly transcendent God. But only Christianity believes that this one transcendent God is love.

For most Christians, this week — Holy Week — is the most important week of the year.

Holy Week culminates in the Paschal Triduum, the three days commemorating the crucifixion, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ. Many Christians prepare for this event with 40 days of fasting, prayer, and alms giving.

Jesus had his last meal — a Jewish Passover meal — with his disciples on the evening of a Thursday (commemorated as Holy Thursday), was arrested during the night, tried Friday morning (Good Friday), and condemned, crucified, and dead before sundown on Friday. And, according to the Gospel accounts, he was bodily raised from the dead on the third day — Sunday, the day of Easter.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Now, it's probably straightforward enough why we Christians would commemorate the crucifixion and resurrection of the one who we believe to be the Son of God. But what about Holy Thursday? Why does his last meal matter so much?

On this, viewpoints differ among Christians. But for the majority — Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, and several other denominations — Holy Thursday is very important because it is the commemoration of perhaps the most implausible of Christianity's long list of implausible beliefs, namely that the consecrated bread and wine that we consume in church is the body and blood of Jesus Christ.

Not metaphorically. Not symbolically. Not conceptually. But actually, really, in the most literal way, flesh and blood. Even though there is not a shred of empirical evidence for this idea, and even though the bread really does look and taste just like any other piece of bread, and the wine looks and tastes just like wine. But it's not bread anymore, and it's not wine anymore. It's flesh and blood. Of a man who lived and died 2,000 years ago.

I believe this. So do a lot of my fellow Christians. When asked how, we mostly shrug our shoulders. Suffice it to say that if you believe God created the whole universe out of nothing, you believe He can do a lot of things that seem — are — impossible, even preposterous.

Many Christians who believe this bizarre doctrine of the Eucharist (myself included) find themselves very attached to it. Often because we have found it true in our lives that the consecrated bread and wine is, in the words of Pope Francis, a powerful spiritual medicine. It has helped us overcome difficulties, and helped us experience God's presence.

Or just because it means that we can touch God — again — in the most literal way. And we can make Him be part of us. There is something carnal, intimate, almost sexual even, to this idea of touching and tasting God. It's a reminder that God is not so much to be understood (indeed, He can't be) as to be experienced. The Eucharist also asserts that spiritual realities, rather than visible realities, are the only true realities — the same belief that sends martyrs singing to their execution.

There's another thing: For Christians, the Eucharist is important because it is the most profound manifestation of a fundamental and misunderstood truth about the humility of God. Yes, you read that right.

Christianity is based on the idea that God — not just the Creator of all things, but the source of all being — is humble. We believe that this infinite God decided to become a man. And not only live as a man, but die as a man. And not only die as a man, but die in the most ignominious and disreputable way He could find. And, finally, God is so humble that he decided to be literally present to us, not as some impressive fireworks, but as the most humble thing: A piece of bread, a cup of wine. No pyrotechnics. Just... presence. Invisible to the eyes of reason, and a dim light to the eyes of faith.

If the transcendence of God is hard to comprehend, the humility of this all-transcendent, all-powerful God is like taking the mystery of transcendence and squaring it. How is it that the unfathomably big not only can, but would want to, become unfathomably negligible?

It might help, for a start, to look at our very limited human understanding of power. Man, if I was as powerful as God, I wouldn't take crap from anybody! That is, of course, a laughably creaturely way to think. Even in the schoolyard, we notice that the one who boasts the most, the one who wants to make the biggest show of his (and it is almost always a he) power, is really the least powerful. The truly powerful don't need to boast, and don't seek to awe others with bombast. Perhaps the infinitely powerful have zero need to show or wield power.

The Eucharist shows that God is not only more powerful than we can comprehend, but also more humble than we can comprehend. Who among us would be willing to reduce themselves to almost nothing for the sake of their loved one, especially if the loved one had been so unfaithful? And yet, God does it over and over and over again.

During the Holy Thursday commemorations, the celebrating priest will typically wash the feet of 12 people from the assembly. This is because the Gospel of John describes Jesus performing this very intimate act (particularly in the context of the 1st century Middle East) for his disciples. Washing the feet of men who are not only utterly unworthy of His divine nature, but who would, in a matter of hours, run away and abandon Him to His fate. It seems odd that John is the only Gospel that doesn't record Jesus calling the bread and wine of the meal his flesh and blood. Until you realize that the two are the same. God becoming food and drink for us is like Him washing our feet. It is Him humbling Himself to serve us and cleanse us.

This is the summary of the Christian faith. Several religions believe in a single utterly transcendent God. But only Christianity believes that this one transcendent God is love — not a God who loves, but a God whose very nature is love. And that, being love, this God goes to the end of unreasonableness, the end of the absurd, the end of the unbelievable, not just to save us, but simply to be with us. Simply to wash the feet of His beloved. This is what Christians see in the Eucharist, and this is what Holy Thursday recalls.

Create an account with the same email registered to your subscription to unlock access.

Sign up for Today's Best Articles in your inbox

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry is a writer and fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. His writing has appeared at Forbes, The Atlantic, First Things, Commentary Magazine, The Daily Beast, The Federalist, Quartz, and other places. He lives in Paris with his beloved wife and daughter.

-

UAW scores historic win in South at VW plant

UAW scores historic win in South at VW plantSpeed Read Volkswagen workers in Tennessee have voted to join the United Auto Workers union

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published

-

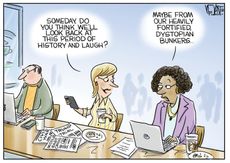

Today's political cartoons - April 22, 2024

Today's political cartoons - April 22, 2024Cartoons Monday's cartoons - dystopian laughs, WNBA salaries, and more

By The Week US Published

-

Ukraine cheers House approval of military aid

Ukraine cheers House approval of military aidSpeed Read Following a lengthy struggle, the House has approved $95 billion in aid for Ukraine and Israel

By Peter Weber, The Week US Published